Wage inequality in postapartheid South Africa

Much work has been done on inequality in South Africa, but to date the literature that assesses the dynamic response of income or wealth distribution to economic policy actions is almost non-existent. This information gap is caused by data shortcomings that make it difficult to provide accurate economic analyses for improving policies. It is necessary to identify time trends and changes in labour earnings so that a more granular picture can shed light on the evolution of inequality in South Africa.

Wage inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient increased in South Africa between 1994–2019

While the richest have become richer, the wage of the poorest 50% has not increased proportionally

Between 1993–2019 the richest 10% earned, on average, about 20 times that earned by the poorest 10% — this gap has remained quite stable over time

During the same period the richest 10% cent earned, on average, about 5 times that earned by the poorest 50% — this gap has almost doubled over the 16 year period

Labour share of income does not seem to be a good indicator for inequality in South Africa, as it is in many developed countries

A robust long-run time series of wage inequality opens up the possibility to study the response of wage distribution to different shocks

Much work has been done on inequality in South Africa, but to date the literature that assesses the dynamic response of income or wealth distribution to economic policy actions is almost non-existent. This information gap is caused by data shortcomings that make it difficult to provide accurate economic analyses for improving policies. It is necessary to identify time trends and changes in labour earnings so that a more granular picture can shed light on the evolution of inequality in South Africa.

Multiple generations of household surveys have been produced since the end of the apartheid regime by local statistical and research agencies. But the nature of the data collected differs more or less substantially in each survey wave because of differences in, for example, the sample design instrument and definitions.

What is needed and presented here is a complete and robust time series which includes corrections on the survey data. This time series lays the ground for analysing, for instance, the impact of monetary policy on wage inequality in South Africa.

The rich have become richer, the wages of the poorest have not increased

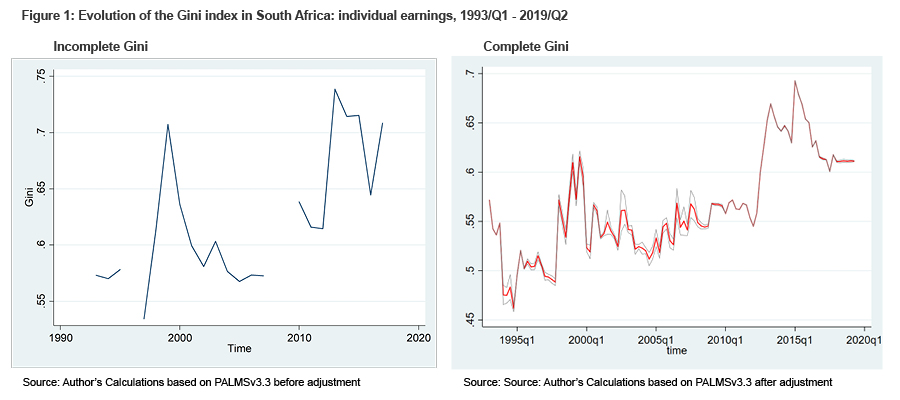

While it is not feasible to fully address all problems pertaining to primary data collection, corrections implemented on national survey data deal with outliers and implausible data records, missing observations at random, bracket responses and sample weights, breaks in the series, underreporting of high incomes, and extrapolation of quarterly frequency observations. Ultimately, inequality is measured here through the Gini index, the most widely cited measure of inequality in thatit satisfies most of the criteria that make a measure of inequality robust. The Gini index is based on pre-tax wage income of individuals in the working age, collected between the first quarter of 2000 and the second quarter of 2019. Figure 1 presents the Gini index time-series derived from national survey data before and after the statistical adjustment adopted by this study. The figure shows that there has been a clear and sustained increase in inequality between 1994–2019.

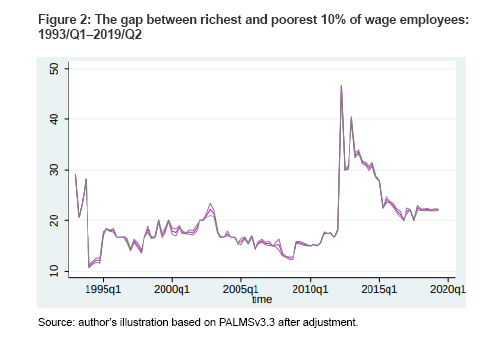

When comparing the share of the richest 10% of workers to the share of the poorest 10% the average ratio over the period 1994–2019 is 19.6 — which means the richest earned about 20 times the amount of the poorest. However there is also an alarming peak in 2012 which is sustained until 2014. This sudden change may be mostly due to methodological issues, given that in 2012 South African officials changed the way they measured key earnings variables. It can also be related to the decline in real GDP growth that corresponds to this period.

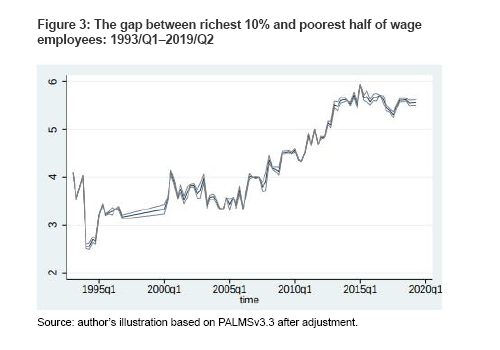

A similar result is found when comparing the income share of the richest 10% with respect to the lower 50% of the wage distribution. The average ratio is 4.7, which implies that the richest receive five times more income than the poorest. Figure 3 shows a positive trend which suggests that the wage differential between the ninth and the fifth decile of the wage distribution has been increasing over time. While the richest have become richer, the wage of the poorest 50 per cent has not increased proportionally. This gap has almost doubled over the 16 year period.

A similar result is found when comparing the income share of the richest 10% with respect to the lower 50% of the wage distribution. The average ratio is 4.7, which implies that the richest receive five times more income than the poorest. Figure 3 shows a positive trend which suggests that the wage differential between the ninth and the fifth decile of the wage distribution has been increasing over time. While the richest have become richer, the wage of the poorest 50 per cent has not increased proportionally. This gap has almost doubled over the 16 year period.

Labour share of income does not reflect well the inequality in South Africa

Labour share of income does not reflect well the inequality in South Africa

Building a coherent picture of inequality in post-apartheid South Africa demands addressing the role of wage or labour share. The notion of wage or labour share refers to the part of national income allocated to workers in the form of monetary compensation as opposed to the part of value added going to the capital input, to the owners of the productive parts of the economy.

In advanced economies a declining labour income share constitutes a major factor in understanding rising inequality. Since labour income is more equally distributed than capital income and represents a higher share of total income for lower- and middle-income groups, when it increases with respect to capital income, the overall distribution improves and inequality lowers.

In South Africa, however, the wage share is found to increase when wage inequality is relatively higher. Given that a big part of the lower end of the labour income distribution is structurally unemployed or economically inactive, this suggests that increasing wages and employment opportunities affect top wage earners relatively more, thus worsening the overall distribution. Hence, the distribution of income is not a good indicator for inequality in South Africa.

To facilitate long-run dynamic policy analysis there remains a need for a more comparable time series of income inequality among wage employees in South Africa. Thus in the future the primary data collection should pay attention to developing long-run and consistent data sets.